Willy Verginer is a contemporary Italian sculptor who turns the old woodcarving culture of Val Gardena into something sharply current. His figures often look calm at first glance – almost classically modeled – yet a sudden block of acrylic color, an impossible object, or a blunt environmental detail tips the scene into quiet absurdity. The result is work that sits between craftsmanship and commentary without becoming theatrical.

Born on February 23, 1957 in Bressanone (Brixen) in South Tyrol, Verginer lives and works in Ortisei, in the Val Gardena area. He studied painting at the Art Institute of Ortisei, then moved deeper into sculpture by working in local wood studios, where generations of carved devotional and decorative work built the region’s reputation.

Those early years mattered because Verginer did not reject tradition so much as outgrow its usual end point. In the 1980s he deliberately distanced himself from conventional methods through self-directed learning, and he later taught at the Professional School of Sculpture in Selva from 1984 to 1989. His first solo exhibitions included abstract works that combined wood with natural materials, before the long pivot toward the figurative language he is best known for today.

A key turning point arrived in 2005, when he presented a radically changed approach at Galleria Castello in Trento. From that moment, carving and acrylic paint became inseparable in his practice, forming what his biography describes as a new and original plastic language. That move helped set the tone for the next phase of his career: realistic bodies, stripped-back expression, and color used as a conceptual cut rather than decoration.

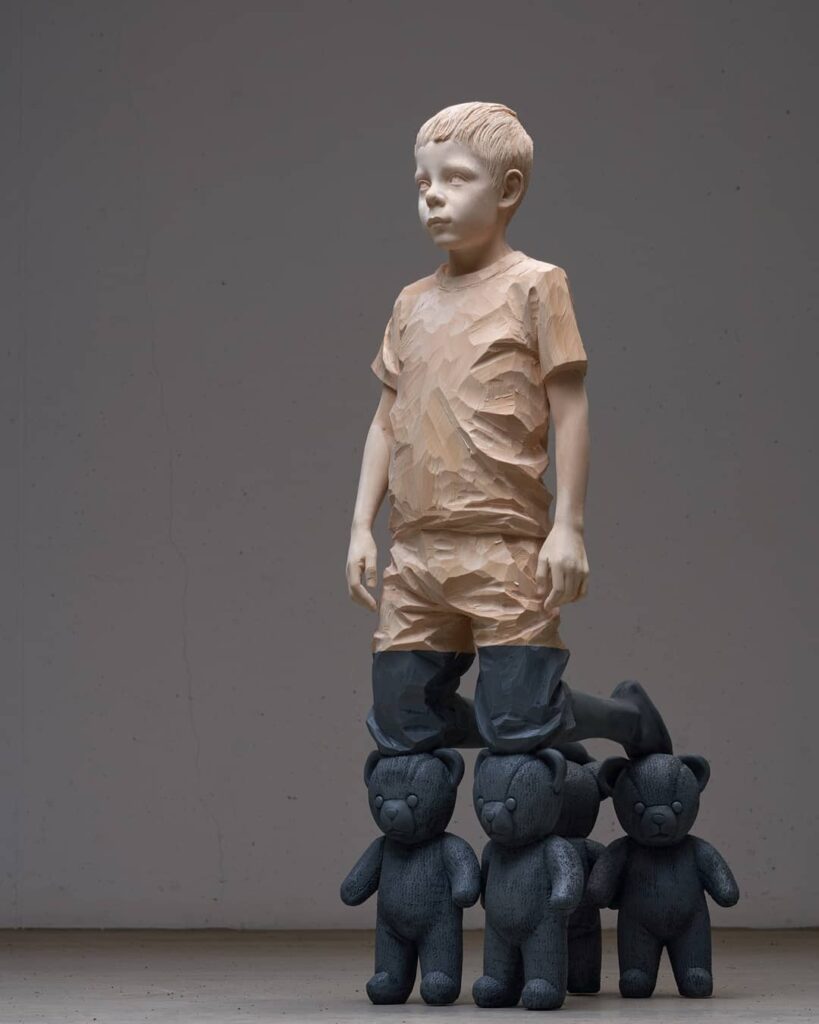

Verginer’s technique is as physical as it is precise. He builds sculptures from multiple blocks of wood that are dried naturally over about six years to reduce warping. Forms are roughed out with a chainsaw and hatchet, then refined with chisels and smaller tools for details like eyelids and ears. The surfaces can feel hyperreal, yet the faces are often intentionally neutral, creating a cool, slightly detached mood even when the carving is tender.

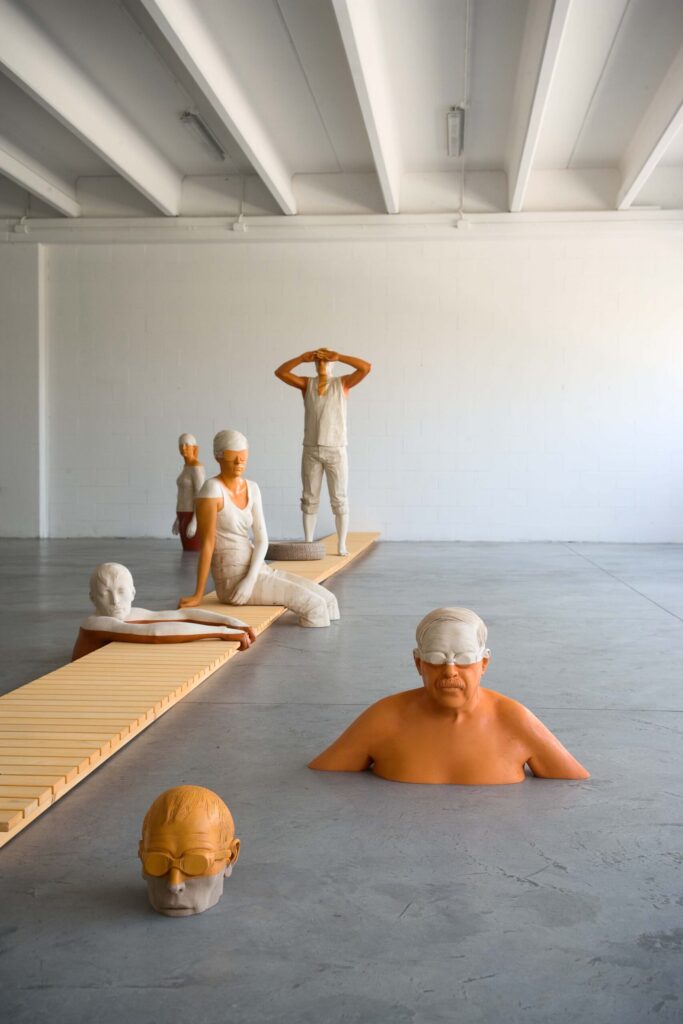

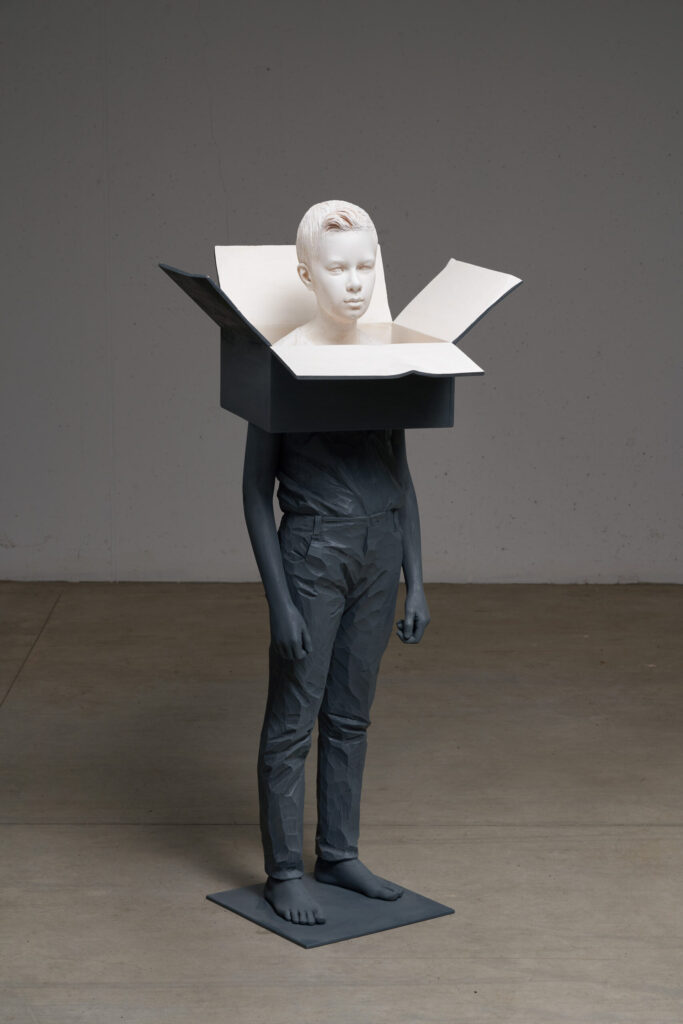

That neutrality becomes the stage for his most recognizable device: a bold, monochrome band or zone of acrylic paint that slices through the figure, sometimes in a clean geometric block and sometimes as a hard horizon. One gallery describes this as a striking chromatic separation that divides each sculpture into two realms – visible and invisible. In practice, it can read like a censor bar, a floodline, a glitch, or a warning label, depending on the scene.

The themes are not abstract in the academic sense. Verginer repeatedly returns to the friction between human life and damaged landscapes, often using symbols that are blunt on purpose. In the series Human Nature, for example, industrial objects like oil drums appear alongside animals and forests, with the metallic idea of the barrel spreading across the composition as a kind of contamination. The irony is controlled: the sculptures stay poised, even when they are pointing at collapse.

His exhibition history tracks the widening reach of this language. Verginer showed BaumHaus at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Lissone, and the cycle also appeared at Biennale Gherdëina with a monumental work under the same title. In 2011, he was invited to the 54th Venice Biennale to represent the Trentino-Alto Adige region, a signal moment for an artist rooted in a small Alpine valley but operating on an international circuit.

Even when the subject matter drifts into dream logic – children interacting with floating spheres, or figures paired with surreal props – the craft never loosens. That tension is part of the point. Verginer’s sculptures borrow the authority of traditional carving and then undermine it with contemporary unease, as if the material itself remembers the past while the painted interruption insists on the present.

What makes his work stick is the restraint. The carving does not need melodrama to feel loaded. A still face, a perfectly cut posture, and one hard band of color can turn a familiar human figure into a quiet argument about where things are headed – and how thin the line is between normal life and the absurd.

Reply