Tugboat Printshop, often shortened to T.B.P.S., is an independent artist press based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, known for publishing original woodcut prints in limited editions. The studio’s focus is traditional relief printmaking – images are drawn by hand, carved into wood, and printed to paper in carefully built layers. It is a practice that values patience and precision over speed, and the finished prints carry the small, honest variations that come with hand production.

The printshop was co-founded in 2006, when artist Valerie Lueth moved to Pittsburgh after buying a house and a press and starting Tugboat Printshop as a serious publishing project. In the early years, Tugboat worked both collaboratively with other printmakers and independently, building a recognizable approach centered on intricate carving and strong composition. Over time, the studio became closely identified with Lueth’s own work, and in 2016 she became the sole owner and operator of T.B.P.S., continuing to run it as a one-artist press.

Tugboat’s identity is tied to the idea of “published” prints rather than casual reproductions. Each new image is developed to exist as an edition, with the same image printed multiple times from the same carved block or blocks. That structure brings discipline to the work. It demands consistent inking, careful alignment, and repeatable results, while still leaving room for the natural character of wood grain, pressure, and ink density to show through.

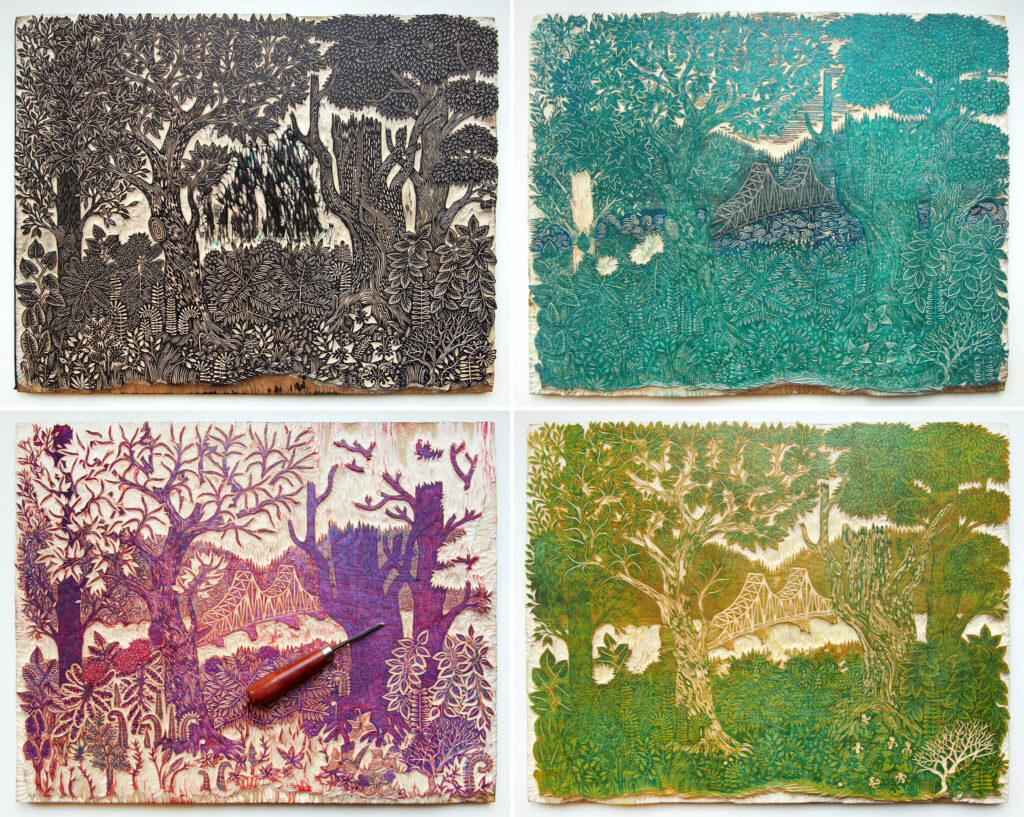

A Tugboat woodcut begins with drawing. The image is planned and then drawn directly onto the woodblock, which is typically 3/4-inch birch plywood. From there, the carving stage translates the drawing into a printable surface. In woodcut, the parts that will stay light are cut away, while the raised areas remain to receive ink. This reversal is part of the mental gymnastics of printmaking: the artist is always thinking in positives and negatives, and in mirrored orientation, because the print will read opposite on the paper.

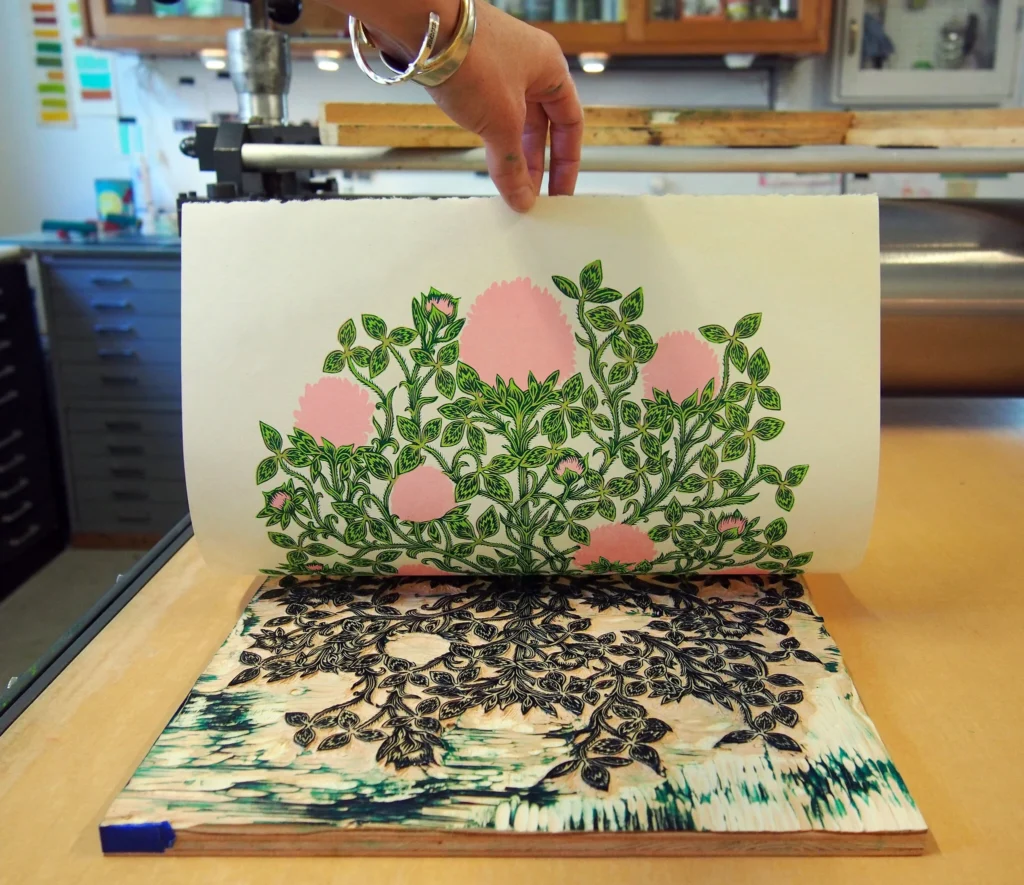

Carving is slow work, especially when the final image relies on fine linework. Clean edges matter. A slight slip can widen a line, and a rough cut can trap ink where it is not wanted. This is why proofing is part of the rhythm. Printmakers often test a block during carving, checking which marks read clearly, which areas need to open up, and where detail might be getting too crowded.

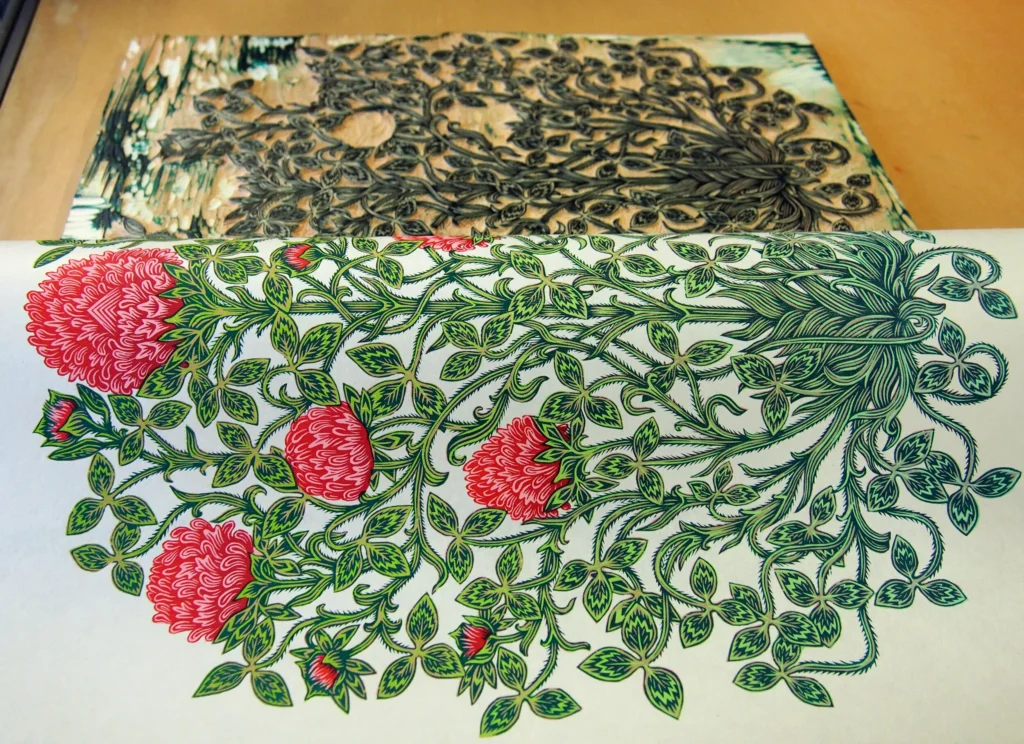

Once a block is ready, inking turns the carved surface into a printing plate. Tugboat uses oil-based inks and prints on archival papers, aiming for richness and longevity. Ink is rolled across the raised surface so it sits evenly on the parts meant to print, without filling the carved recesses. Then paper is placed and printed using steady pressure, producing a single impression. That impression is one step in an edition.

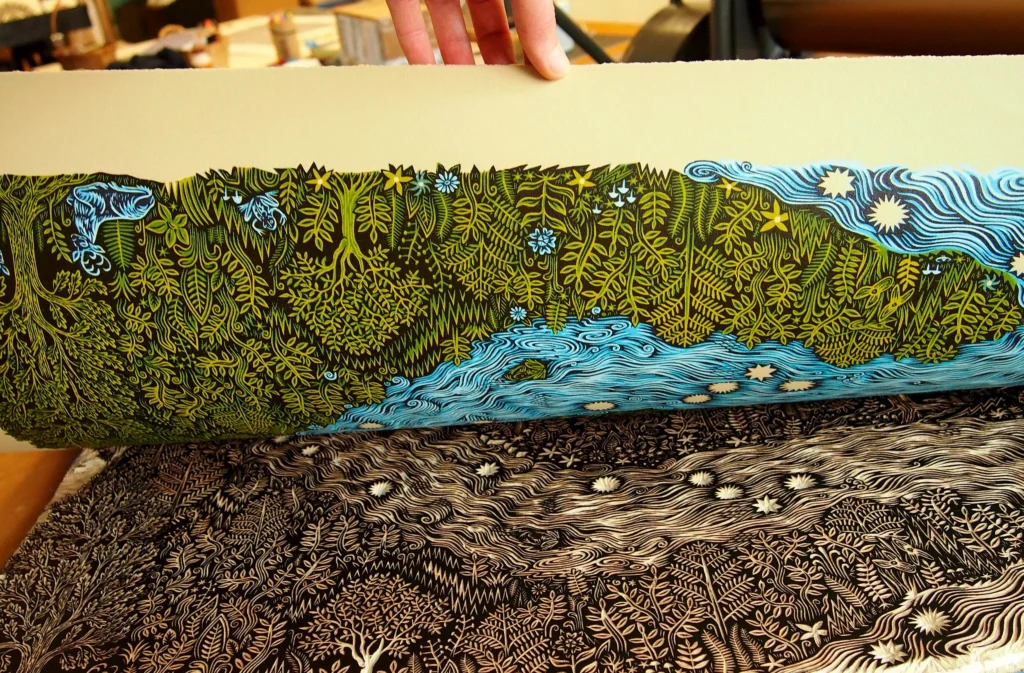

Color adds another layer of complexity, literally. Many Tugboat prints are built from multiple woodblocks, with separate blocks carved for different colors or key details. The image is created through stacked impressions – one layer printed, then another precisely aligned on top, and so on. Because each layer must land in exactly the right place, registration becomes a craft of its own. Even a tiny shift can blur edges or create halos where colors meet, so the setup has to be controlled from the first sheet to the last.

The pace of multi-block printing is demanding. Each sheet moves through the same cycle repeatedly: align, print, dry, repeat for the next color. Overprints can produce new tones and subtle depth, especially when inks are laid in thin layers. The final print is not just a picture, but a record of decisions made across many passes.

When an edition is complete, Tugboat finishes it as a published object. Prints are typically signed, titled, and numbered as part of a limited run. That editioning is what makes the work collectible and traceable, and it reflects the studio’s commitment to printmaking as a serious, old-school form of making images. In a world full of instant reproduction, Tugboat Printshop stands out by doing the opposite: slowing everything down, and letting the process show.

Reply