In the quiet mountain villages of Bavaria and Austria, there’s a kind of hidden poetry carved into the ends of old timbers. It’s called Zierschrot, a word that sounds as textured as the craft itself. “Zier” means ornament, “Schrot” means cut — and together they describe the decorative shaping of log ends and beams in traditional Alpine houses. It’s an art form that hides in plain sight, on the corners of farmhouses, under the eaves of barns, and along the walls where the carpenter’s hand lingered a little longer than necessity demanded.

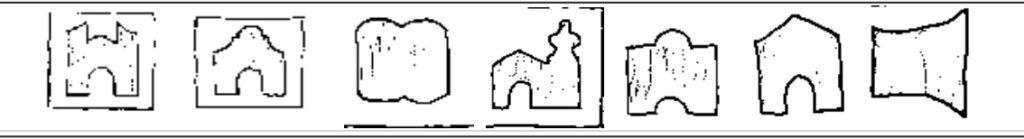

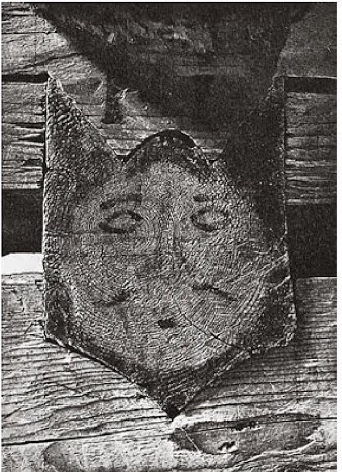

Zierschrot was born from the logic of timber construction. In these old log buildings, the ends of beams naturally projected beyond the wall, visible like punctuation marks in a sentence of stacked wood. They could have been left plain, trimmed square and forgotten. But the Alpine craftsman rarely stopped at “good enough.” Instead, he treated these ends as small canvases, carving them into hearts, crosses, animal shapes, or symbols known only to the maker. Sometimes he painted them, sometimes he left them bare to silver with age and weather. Each cut carried both purpose and pride — a whisper of beauty added to structure.

There’s something almost philosophical in that gesture. The carpenter had already tamed the tree, hewed it to fit, joined it tight. But to carve into the end grain was to leave a mark of self — not a signature, exactly, but a kind of dialogue with the material. The wood was already alive with grain and story, and the craftsman simply added a few human sentences to it. Maybe it was superstition, maybe vanity, maybe pure joy. Whatever the reason, Zierschrot turned the structural into the personal, the ordinary into something quietly transcendent.

Wander through an old Tyrolean hamlet and you might still find these details, faded but stubbornly intact. A log end carved like a church silhouette on a farmhouse gable. Another shaped into the form of a stag, the body made from the timber’s own end, the head and legs applied later. They seem playful at first — rustic doodles in oak and fir — but look closer and you’ll sense the discipline beneath the whimsy. These weren’t careless carvings. They were balanced compositions, done with an understanding of the wood’s grain and strength. Even the most fanciful form still respected the beam’s duty to bear weight and hold fast.

Zierschrot is a reminder of how deeply the old builders valued beauty, even in places few might notice. The log end isn’t a decorative flourish added after the fact; it’s part of the architecture itself. The carpenter didn’t separate craft from art — they were the same act. The building held up a roof, yes, but it also held up a kind of cultural memory. Each ornament was a signal: here lived someone who cared about their work, someone who believed that structure and soul belonged together.

Today, when woodworking has largely become a game of clean edges and efficiency, Zierschrot feels like a gentle rebellion. It’s the opposite of minimalism. It invites us to slow down, to decorate not for fashion but for connection. Modern builders can still learn from that spirit. You don’t have to carve a cathedral into every beam, but you can remember that even a small gesture — a chamfer, a texture, a carved symbol — can turn an object from something made into something lived with. Zierschrot teaches that beauty belongs in the working parts, not just the surfaces we show off.

There’s also a deeper respect for the wood itself hidden in this old practice. One craftsman once wrote that because mankind interrupts the life of the tree by felling it, we owe it our care in return — to handle it with reverence, to preserve it through craft. In that sense, Zierschrot isn’t just decoration; it’s a small act of gratitude carved into the very bones of a building.

Perhaps that’s why the old houses feel so human. You can walk through an Alpine valley and read them like stories. The beams and carvings speak across time, the way handwriting does on a letter from a stranger who somehow feels like a friend. Every Zierschrot is a kind of handshake between maker and wood, between necessity and imagination.

And maybe that’s what we miss in modern construction — that handshake, that pause between the last strike of the chisel and the first breath of admiration. In the carved ends of a Bavarian farmhouse, a beam becomes more than structure. It becomes an idea — that even the most practical things deserve a touch of grace.

Reply