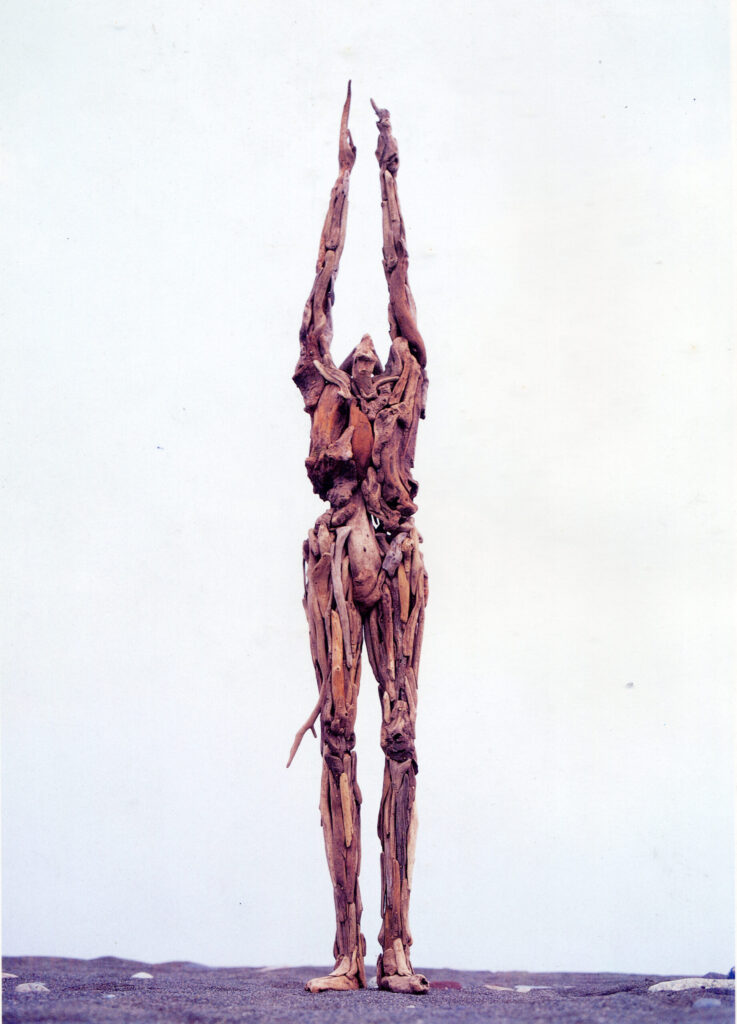

Nagato Iwasaki’s driftwood figures look as if they have just stepped out of the forest and paused mid stride. Life sized, anonymous, almost anatomical, they sit right on the line between sculpture and apparition. For more than two decades the Japanese artist has built an entire world of humanoid forms from pieces of found wood, a body of work he simply calls Torso.

A sculptor who lets the work speak

There is unusually little public information about Nagato Iwasaki himself. Even detailed features in Japanese and international media point out that his website and social channels reveal almost nothing about his biography, training or personal story. What emerges instead is an artist who prefers to stay outside the spotlight and let the sculptures carry the narrative.

What is known is that he draws, paints and experiments with digital art, and that his first exhibition dates back to the early eighties. In the decades that followed, he has shown work in Tokyo, Germany and at international events such as the Florence Biennale, including a collaboration with fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto.

Torso: bodies made from the shore

The core of Iwasaki’s work is Torso, a long running series of human figures made entirely from driftwood collected around Japan. The project began in the mid nineties and continued for roughly twenty five years.

Each piece starts with foraged wood shaped by salt, sun and water. The artist chooses fragments whose curves already suggest muscles, tendons or bones. In a rare comment on his process he described himself as gathering pieces of wood like an insect building a nest, slowly assembling them into full sized bodies around 180 centimeters tall.

Seen up close, the sculptures are a dense map of joints and overlaps, every strand of wood fitted to echo a rib, a shoulder blade or the twist of a spine. Some figures are complete, with simplified heads and an almost smooth skin of driftwood. Others are cut at the waist or missing limbs, as if they are dissolving into the landscape.

Between forest, river and gallery

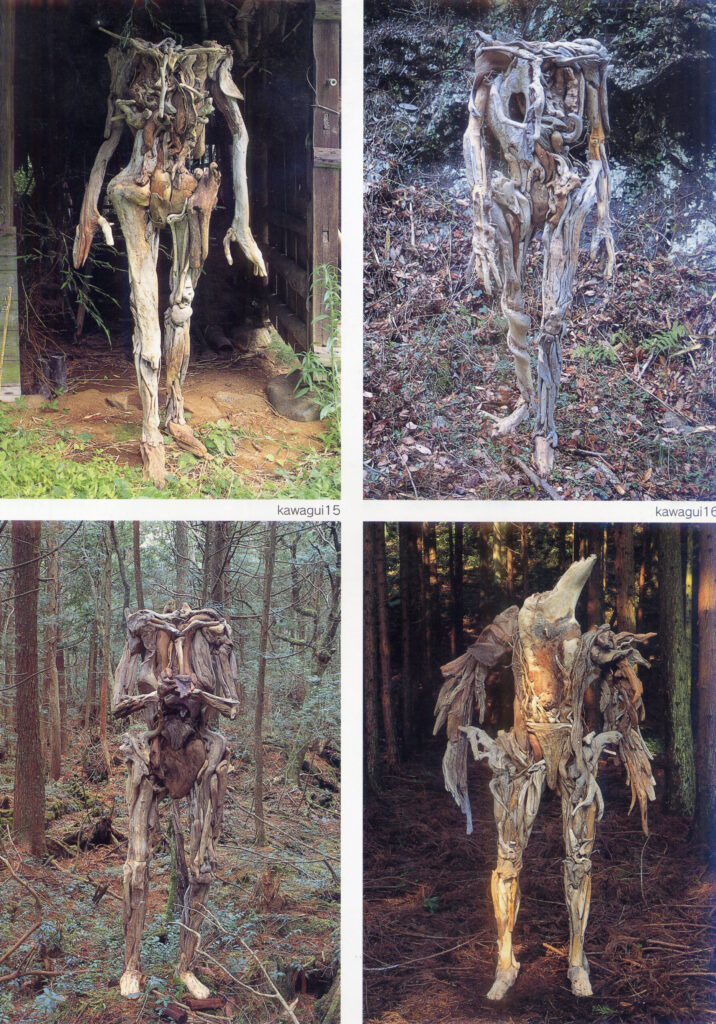

Iwasaki rarely presents his work as isolated objects on neutral plinths. Instead, Torso was conceived from the start as a series that would inhabit real places. Finished sculptures are carried back into nature and photographed or installed in forests, marshes and along rivers, where they stand in shallow water or on stones like silent sentries.

In these settings the driftwood bodies can be read both as visitors and as something grown from the landscape itself, made from the very material carried down by the currents. When the same figures are brought indoors, into museums or galleries in Tokyo and abroad, they feel different again, like strange guests from another environment who have wandered into the white cube.

Over the years, parts of Torso have appeared in numerous exhibitions. The sculptures have been shown across Japan and internationally, and at the Florence Biennale they were presented alongside Yohji Yamamoto’s designs. One of the pieces even appeared on the cover of an album by the Tokyo rock band The Back Horn.

The uncanny edge

Writers who cover Iwasaki’s work consistently describe the figures as unsettling, eerie or otherworldly. They sit inside the uncanny valley, that uncomfortable space where something non human appears almost, but not quite, like a real body.

From one angle they look muscular and powerful, with torsos that seem to flex under an invisible skin. From another, the hollow spaces between the wood pieces open up like wounds. There are no faces, no eyes to meet, only blank surfaces and hints of organs and bones laid out on the outside of the body.

Yet there is also a sense of vulnerability. Many figures are slightly hunched or tilted, almost as if caught in mid gesture, and the pale wood carries the marks of the sea and the weather. That combination of presence and fragility is a large part of what gives Torso its emotional impact.

An open work

Because Iwasaki offers so little explicit explanation, Torso remains open to interpretation. Some viewers read the sculptures as environmental commentary, built from material washed up on the shore and returned to forests and riverbeds. Others focus on the psychological charge of the figures, seeing them as stand ins for memory, trauma or the thin border between life and death.

The artist, however, seems content to leave those meanings unresolved. By withholding biography and long statements, he allows the works to circulate almost as anonymous presences, inviting each person to draw their own conclusions while confronting these driftwood bodies in nature or under gallery lights.

What is certain is that Nagato Iwasaki has carved out a distinct place in contemporary wood sculpture. Through patient collecting, precise assembly and a deliberate play between figure and environment, he has turned discarded fragments of shoreline timber into one of the most striking explorations of the human form in recent decades.

Reply