John Makepeace: A Master Craftsman Reshaping British Furniture Design

John Makepeace stands as one of the most influential figures in contemporary British furniture design. Born on 6 July 1939 in Solihull, Warwickshire, he has dedicated more than six decades to transforming how we think about wood, craftsmanship, and the very language of furniture. Often called “the father of British furniture design”, his work bridges the gap between traditional woodworking and sculptural art.

Early Life and the Discovery of a Calling

Makepeace’s relationship with wood began remarkably early. As a young child, he was fascinated by three pieces of furniture at home – items he later discovered were made by his grandfather. By the age of seven, he was already working with wood himself. A pivotal moment came at eleven when he visited a furniture maker’s workshop and saw fine craftsmanship up close for the first time. During his teenage years, trips to Copenhagen introduced him to the great Danish cabinet makers, which profoundly shaped his design sensibilities.

When his father died in 1957, young John made a decisive choice. He set aside thoughts of entering the church and instead pursued furniture making as his profession. He trained with Keith Cooper in Dorset while studying through distance learning to qualify as a teacher. By 1961, at just twenty‑two years old, he had established his own workshop.

Building a Reputation

The early years brought modest local commissions, but Makepeace’s talent soon attracted attention from major retailers. His designs appeared in Heal’s, Liberty’s, and Harrods. A coffee table he designed casually one weekend became an unexpected commercial hit – Habitat eventually ordered them by the container load.

Yet commercial success was not what drove him. In the mid‑1970s, Makepeace made a deliberate decision to step back from mass production and focus on individual pieces that could never be replicated by machines. He wanted to create furniture as art, not product. His philosophy centred on designing pieces that were lighter, stronger and more sculptural forms better suited to their function.

Major institutional commissions followed. Liberty’s commissioned him for their Centenary Dining Room. Keble College at Oxford hired him to furnish 120 rooms. Boardrooms for Kodak, Grosvenor Estates, and Banque du Luxembourg showcased his work. Museums began acquiring his pieces – the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the Fitzwilliam in Cambridge, and the Art Institute of Chicago all added Makepeace creations to their collections.

The Parnham College Revolution

What frustrated Makepeace was the state of design education in Britain. The system separated practical skills from creative thinking from business knowledge – an approach he considered fundamentally flawed. In 1976, he took a bold step. He purchased Parnham House, an eighty‑room Tudor mansion in Dorset, and founded the School for Craftsmen in Wood, which opened in September 1977.

The school offered something revolutionary: an integrated curriculum combining design theory, hands‑on making skills, and business management. Students emerged not just as craftspeople but as entrepreneurs capable of sustaining themselves through their work. Guest lecturers from engineering, automata, and various design fields broadened students’ perspectives.

Over its twenty‑five‑year existence, Parnham College produced hundreds of talented furniture designers and makers. Its alumni include David Linley, furniture maker and chairman of Christie’s UK, who has said that he owes his career to the many people John Makepeace brought together to revitalise the modern Arts & Crafts Movement. Other notable graduates include internationally recognised designers such as Konstantin Gric, Sean Sutcliffe, and Jake Phipps.

Hooke Park and Sustainable Forestry

Makepeace’s vision extended beyond furniture to the very source of his materials. A commission for Longleat House introduced him to excellent forest management, and he became convinced that better understanding of woodland resources would benefit both design and the environment.

In 1983, the Parnham Trust purchased Hooke Park, a 350‑acre woodland near Beaminster. This became a centre for research into how forest produce could be better utilised. Working with world‑class architects and engineers – including Pritzker Prize laureate Frei Otto and Edward Cullinan – Makepeace oversaw the creation of award‑winning buildings using small‑diameter timber from forest thinnings. These structures demonstrated that materials often considered waste could create innovative architecture.

When Makepeace stepped back from directing the Trust in 2000, Hooke Park amalgamated with the Architectural Association, which continues to run design and construction courses there today.

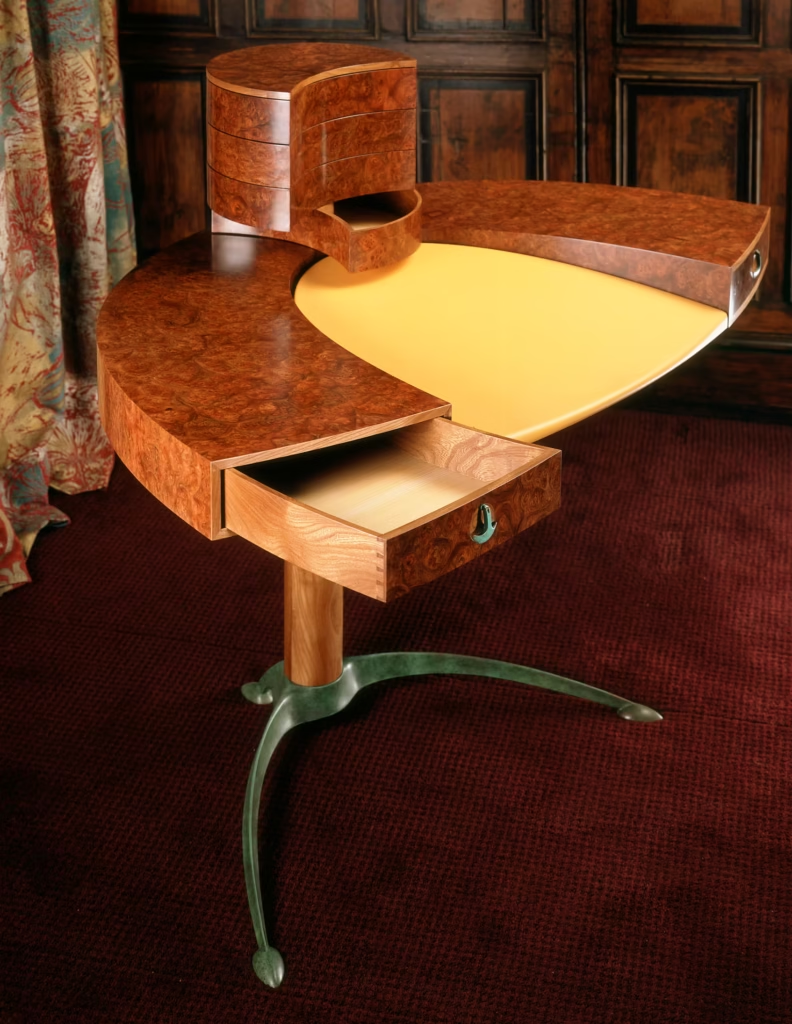

Design Philosophy and Notable Works

Makepeace’s furniture defies easy categorisation. He pushes both aesthetic and technical boundaries, making ambitious use of lamination and mixing materials freely – wood, leather, metal – while always letting wood take centre stage. His “Column of Drawers” from 1978, with birch and coloured acrylic drawers cantilevered from a stainless steel spine, sits in the Victoria & Albert Museum collection as an example of sculptural storage.

His three‑legged Trine chairs demonstrate his willingness to embrace cutting‑edge technology. Their internal metal connections are adapted from technology originally developed for wind turbine blades in Hawaii. The chairs appear enigmatically balanced, challenging assumptions about what furniture can look like while remaining perfectly functional.

Each commission takes between six and eighteen months to complete. Makepeace refuses to rush, and he does not accept strict guidelines about how pieces should look. If a client wants something very specific, he prefers to send them elsewhere. A pair of his Mitre chairs, originally sold for £2,000 in 1977, later appreciated dramatically in value.

Recognition and Continuing Legacy

The honours Makepeace has received reflect his influence. He was awarded an OBE in 1988 for services to furniture design. The American Furniture Society later gave him an Award of Distinction and a Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2016, he received the prestigious Prince Philip Designers Prize for his contributions to professional practice, education, and public appreciation of design.

Now in his mid‑eighties, Makepeace continues working from Farrs, his historic home in Beaminster. He still takes on commissions for clients in the UK and abroad, and he has supported projects exploring regenerative practices and the future of natural materials. His career truly has been, in his own words, an adventure in wood. Through his designs, his teaching, and his environmental vision, John Makepeace has changed not just British furniture, but the way generations of designers approach their craft.

Reply