Jeffro Uitto: The Driftwood Alchemist of Tokeland

In the small coastal town of Tokeland, Washington, where the Pacific wind carries salt and seaweed through the streets and gulls cry above empty beaches, a workshop hums quietly with transformation. Inside, among piles of bleached roots, twisted branches, and wave-smoothed logs, artist Jeffro Uitto coaxes life back into wood that has already lived a dozen lives. What was once a tangle of driftwood on a storm-tossed shore becomes a horse rearing mid-stride, an eagle about to take flight, a rhino heavy with quiet power.

To walk into Uitto’s studio — known to locals as Knock on Wood — is to enter a living conversation between man and nature. The scent of cedar, fir, and salt air mingles with the faint echo of surf outside. Here, nature’s leftovers are given new voices, their silent histories retold in sculpture, furniture, and form.

The Artist by the Sea

Jeffro Uitto was born and raised on the Washington coast, a world shaped by weather and wilderness. Tokeland sits on the edge of Willapa Bay, a place where rivers meet the sea, where forests lean toward the wind and every storm leaves a mark. For a child with a fascination for form and texture, it was an open-air classroom. “The ocean was just a block or two away,” he once recalled. “Everything I needed was right there.”

From an early age, he was drawn to making things — forts from fallen logs, carvings from driftwood, small pieces of furniture with rough edges and big imagination. Over time, that boyish play turned into craft, and the craft into something approaching devotion. Even now, decades later, Uitto still roams the beaches after storms, eyes scanning for the right shape in a tangle of roots or a shard of weathered trunk. “Sometimes the wood inspires the idea,” he says, “and sometimes I go looking for the wood that matches the vision.”

Listening to the Wood

Driftwood is a peculiar material. It’s wood that’s been stripped of its history but not its character. It carries salt scars and water stains, knots smoothed by the ocean’s patience. Where most see debris, Uitto sees anatomy — the curve of a neck, the turn of a flank, the gesture of motion locked in wood grain.

Back in his workshop, pieces accumulate like stories waiting to be told. He rarely begins with a detailed plan. Instead, he studies the wood until it speaks back. A branch might suggest the arch of a spine; a root might recall the sweep of a wing. Bit by bit, he brings these found fragments together, allowing them to reveal what they were always meant to become.

He doesn’t force them into shape; he collaborates with them. His process feels more like discovery than construction — a dialogue between driftwood and intuition. “Each piece already knows what it wants to be,” he once said. “My job is to listen closely enough to find out.”

When Wood Becomes Motion

The result of that conversation is art that seems alive. Uitto’s driftwood horses, for instance, are miracles of movement — bodies built from countless individual pieces that twist and coil like sinew, every curve suggesting muscle and breath. The surface of the wood carries a wild, tactile beauty: rough edges, soft curves, and a memory of the sea.

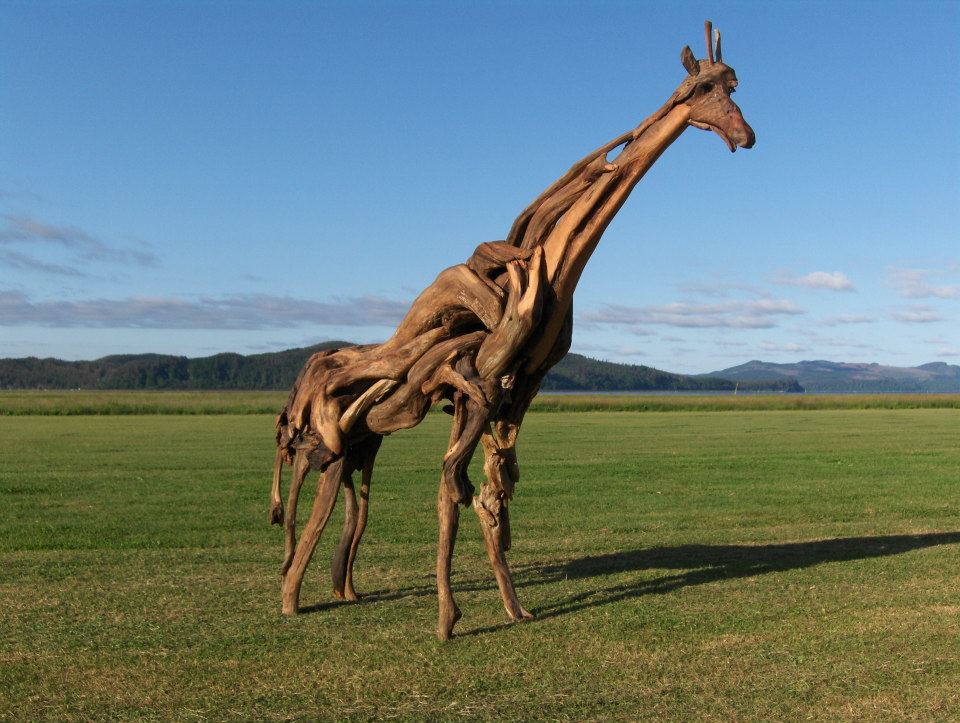

His eagles seem mid-flight, feathers unfolding from long shards of cedar. His giraffes stretch gracefully skyward, their long necks formed from branches that seem to have grown precisely for that purpose. Even when his subjects stand still, they possess momentum, as if the tide might tug them back into motion at any moment.

To Uitto, the goal is not perfect realism. It’s spirit — that invisible force that makes something feel alive. In his hands, driftwood becomes muscle, gesture, breath. “I want people to feel energy,” he explains. “Like the piece could move if you turned away.”

Driftwood as Memory

Every sculpture begins as a scavenger’s treasure hunt. After Pacific storms, when the beaches are scattered with uprooted trees and sun-bleached branches, Jeffro sets out in search of his next collaborator. The wood comes from river mouths, forest creeks, and open coastlines. Some pieces have traveled miles; some may have drifted for years.

He collects them, cleans them, and lets them dry — sometimes for months, sometimes for years. Each fragment is catalogued not by number but by feel: the twist of a root, the color of bark, the curve of a grain. These are materials with stories embedded deep within. The sculptures that emerge are, in a way, a kind of memory work — an act of resurrection.

When his pieces finally come together, the viewer senses this lineage. The wood still feels like it belongs to the sea, and yet it’s reborn into something terrestrial, almost mythic. His sculptures are hybrids of past and present — part forest, part ocean, part imagination.

Between Art and Craft

Although his work is often displayed in galleries and museums, Uitto’s foundation remains deeply physical, even carpentry-like. His studio is filled with handmade tools, clamps, and chisels. He knows how wood behaves — how it shrinks and expands, how to join uneven surfaces without compromising their raw integrity.

He works slowly, piece by piece, joining roots and trunks through hidden dowels or natural interlocking. No two surfaces are ever the same, and no joint is perfectly planned. “It’s all feel,” he says. “You can’t force driftwood to fit. You find where it wants to go.”

The discipline of woodworking grounds his art. Beneath the lyricism and texture is an understanding of grain, weight, and balance. His sculptures may look effortless, but they are engineered through patient craft and deep respect for material.

In that sense, Uitto’s practice bridges two worlds — fine art and woodworking. The first gives him the freedom to dream; the second gives him the means to make those dreams stand.

The Furniture That Breathes

Not all of Uitto’s creations are animals. Some are furniture pieces — benches, chairs, tables — but even these refuse to behave like traditional carpentry. A chair might grow from a tangle of roots, its arms curved and organic. A table might appear as if grown from the earth, its legs thick and gnarled. Each carries the same lifelike presence as his sculptures, the same respect for imperfection.

These pieces seem to breathe. They’re not cut to measure or polished to uniformity; they’re shaped by feel, balanced between usability and poetry. To sit in one of his driftwood chairs is to rest inside a piece of living sculpture, to feel both the sturdiness of timber and the wildness of the coast.

Recognition and Reach

Over the past decade, Uitto’s work has gained international recognition. His sculptures have been shown in galleries across the United States and abroad, and one of his most celebrated pieces — a massive driftwood rhinoceros — found its way to the Chimei Museum in Taiwan. It was a project years in the making, built from wood he had saved for just the right occasion.

Yet despite the acclaim, he’s remained rooted in Tokeland, the small town that shaped his outlook. His studio is part workshop, part museum, part driftwood sanctuary. Visitors still drop by unannounced, drawn by word of mouth and the quiet magnetism of his work. There’s no glamour, no industrial production — just the rhythm of tide and timber, the patient choreography of art made by hand.

Art Born from Place

There’s something unmistakably Pacific Northwest about Uitto’s art. The forms, the textures, the way the sculptures seem carved by weather rather than tools — they all echo the coastline itself. His materials come from that environment, and his sensibility grows out of it.

Tokeland is a humble dot on the map, but its wild beauty is palpable: fog hanging low over spruce trees, waves breaking on long stretches of sand, the scent of rain-soaked earth. You can feel those elements in Uitto’s sculptures — the wind-swept lines, the salt-polished surfaces, the patience of a tide that shapes everything it touches.

His art, in that way, is not only about animals or furniture. It’s a portrait of the coast itself. Each curve of driftwood carries the signature of its environment. Every sculpture is a geography of grain and tide.

The Quiet Philosophy

Though Uitto doesn’t describe himself as an environmentalist in a formal sense, his practice carries an unspoken message about sustainability and reverence. He doesn’t buy new timber or clear-cut logs. Everything he uses has been discarded by nature — already shaped, already offered.

By giving new life to what the sea leaves behind, he reminds us of the cycles of transformation that surround us. Nothing is ever truly lost; it just changes form. Driftwood becomes sculpture, storm damage becomes beauty. It’s art as restoration — not of the material, but of perspective.

There’s humility in that, too. “The outcome is beyond me,” he admits. “I just try to show up and do my part.”

The Rhythm of Making

Inside his studio, time stretches. There’s no rush, no countdown to completion. Uitto works until the sculpture feels right, sometimes setting it aside for weeks, then returning when the shape reveals itself. Music plays softly in the background; sawdust settles on the floor like snow.

He speaks of those moments of focus as something meditative. “You get so dialed in that time doesn’t even exist,” he says. “You’re a vessel, and energy just moves through you.”

Watching him assemble a large piece is like watching a slow dance between instinct and patience. Each addition changes the rhythm; each connection alters the flow. He moves around the sculpture constantly, studying it from every side, making small adjustments until it seems to breathe on its own.

The Driftwood Menagerie

Over the years, Uitto’s body of work has grown into a kind of wooden menagerie. Horses, lions, giraffes, longhorns, eagles, rhinos — each one different, yet connected by a shared pulse. They seem like mythological creatures made of tide and time, their surfaces carrying both fragility and strength.

They’ve appeared in galleries, private collections, and online exhibitions, often stopping viewers in their tracks. Photographs never quite capture the presence of these works — the way light glances off grain, the way shadow fills the hollows between pieces. In person, they feel monumental yet intimate, raw yet graceful.

His animals don’t imitate nature; they reinterpret it. They carry the chaos of driftwood and the order of anatomy, meeting somewhere in the middle — a place where wildness becomes form.

The Artist’s World

When he’s not sculpting, Uitto still spends his days much the same way he did as a boy — wandering beaches, exploring forests, fixing up his studio. He shares the space with his partner, artist Zela McKinstry, whose creative input often shapes new ideas. Together they blend practicality with imagination, keeping the studio buzzing with projects both monumental and small.

Despite growing attention, Uitto’s world remains resolutely local. He supports nearby art communities, mentors younger makers, and shows his work at coastal events. To him, the act of creation is not about fame, but about connection — to material, to landscape, to the rhythm of life on the water’s edge.

The Meaning in the Material

At its heart, Uitto’s art carries an invitation: to see the world differently. To recognize beauty in what’s been discarded, to value imperfection, to let nature lead the way. In a world of uniform design and digital perfection, his driftwood sculptures feel refreshingly imperfect — rough, irregular, unapologetically real.

Standing before one of his pieces, you can trace the journey of the wood itself — from tree to river, from ocean to shore, from ruin to renewal. It’s a reminder that transformation is constant, that even what seems broken or lost can be shaped into something extraordinary.

Perhaps that’s why his work resonates so deeply. It isn’t just about what he builds — it’s about what he restores in us: a sense of wonder, patience, and reverence for the natural world.

From Shoreline to Spirit

Jeffro Uitto has built a career out of listening — to the waves, to the wind, to the silent intentions of wood shaped by the sea. His sculptures may begin as debris, but they end as gestures of life, memory, and motion.

In every curve, there’s the echo of the ocean; in every joint, the patience of time. And when you stand before one of his driftwood creatures, you feel the world slow down just enough to remind you that art, at its best, doesn’t invent — it reveals.

Reply