In the small Lithuanian village of Bubiai, surrounded by the calm landscapes of Šiauliai district, stands a house that seems to have grown from the land itself – warm, rounded, and alive with oak. This is the home and studio of Rimas Navickas, a man whose furniture carries the soul of trees, the rhythm of nature, and the influence of the great Antoni Gaudí. To step into his home is to enter a world where oak breathes, curves replace corners, and every piece of furniture tells a story of patience, faith, and love.

Rimas works only with naturally dried solid oak, material that has already reached balance with air and time. He says he could never bring himself to cut down a living oak – the tree is too noble, too sacred – but if others have done it, then it must not be wasted. From such wood, he believes, only the most beautiful things should be made. “If the oak has been taken,” he says, “let it live again in something worthy.” His furniture embodies this vow: it is strong yet delicate, monumental yet soft, with carvings that look like lace, as if oak were spun from thread.

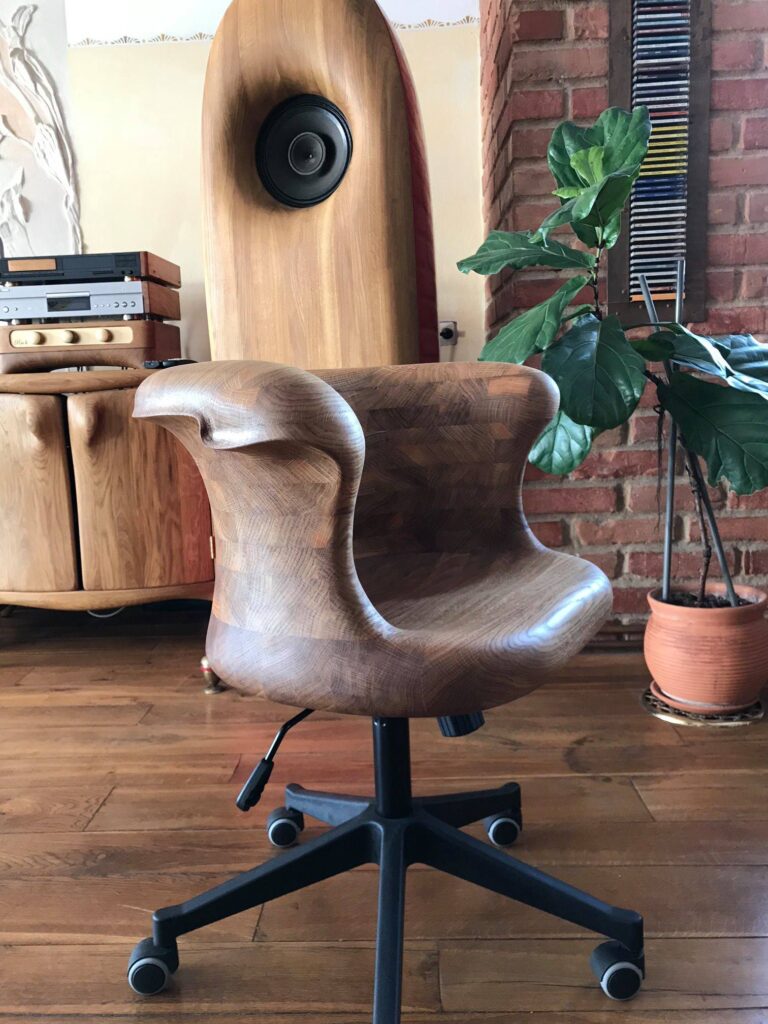

His technique – a personal method with no formal name – produces furniture that appears sculpted by wind and patience rather than by tools. Every table, chair, and cabinet is a one-off, each slightly different from the next, as if the tree’s spirit decided its final shape. When sunlight touches the carved surfaces, shadows bloom inside the patterns, making the wood look light as paper. Visitors often describe his work as “oak lace.”

Navickas’s story began with an accident that changed everything. In 1986, an old, broken armchair somehow found its way into his home. It was too beautiful to discard, though it was nearly beyond repair. His family laughed when he said he would restore it – he had never held a chisel before. Yet he set to work, and when time had eaten parts of the chair beyond saving, he simply recreated them. That restoration awakened something in him. The chair’s openwork carvings became his lifelong signature, and his first encounter with oak turned into a calling that has lasted decades.

From that first piece, his hands never stopped carving. His home became a gallery of wood: oak floors, oak beams, oak window frames, every surface alive with texture and meaning. Nothing here is accidental. His furniture has no sharp corners; every form flows like a river. He studied feng shui, and the philosophy seeped into his craft – soft edges, balanced energies, shapes that calm the mind. But the deepest source of inspiration came later, when he discovered Antonio Gaudí. “Nature has no straight lines,” Gaudí said, and Rimas took those words as his own compass. “In the East they say that an orphan is not one without parents, but one without a teacher,” he explains. “I am not an orphan. My teacher is Antoni.”

Even the structural post that holds his hallway ceiling became art: he carved it with the yin and yang symbol, its lines rising and descending like energy currents between earth and sky. When asked how he designs, he says simply, “I listen to my heart first.” In his bedroom furniture you can see echoes of ancient civilizations – serpents curling along headboards, elephant trunks forming table legs – details inspired by the Incas and the Maya. Each symbol has a meaning. Nothing is for decoration alone. His furniture seems alive, the way living things are – it breathes, it moves with the light, it invites touch.

At first, he vowed never to make kitchen furniture, thinking it dull and repetitive. But one day he laughed at his own promise: “You should never say never – the water you spit into is the one you’ll drink.” Today, his kitchen is a marvel of carved oak: cabinets, chairs, even a breadbox and a water tap shaped by hand. He jokes that his oak chairs “heal the spine and even hemorrhoids,” but behind the humor is a maker’s truth – his furniture fits the body naturally. He somehow knows, without measuring, what makes a chair comfortable or a table inviting.

His relationship with oak is not only practical; it is spiritual. He believes the wood carries energy that can heal. His children sleep in oak beds and never complain of hardness. The surfaces in his home are finished only with natural oils made from plants. “Lacquer is like plastic,” he says. “It kills the wood. Oil lets it live.” When an oiled surface wears, he renews it by hand, rubbing new oil into the grain – a small act of maintenance that feels more like care than repair.

The devotion goes even further. Unable to cut down oaks himself, he and his family planted nearly a thousand new ones on their land between Vijurkai and Lupikai. Together they are creating an oak park – a living cathedral of trees – that will one day hold five thousand specimens. They didn’t apply for government aid; their dream didn’t fit the official definitions. “They would have allowed us to plant a forest,” he says, “but we wanted a park.” On a hill, they planted a ring of eighteen oaks, from which nine paths of trees extend like rays of a sun – each number symbolic, each line meaningful. The park now spreads across eight hectares and will eventually double. Neighbors sometimes wonder why they labor so hard over trees they won’t live to see grown. Rimas just smiles: “We’re not living only for today. What matters is what we leave behind.”

Everything he builds, everything he touches, radiates this philosophy – the belief that love and intention are inseparable from craft. Without love, he says, there would be no art, no furniture, no life worth shaping. His wife Rita, a musician, fills their home with sound. Even her speakers are mounted on oak panels carved by Rimas, because, he insists, sound resonates more purely through wood. “It touches the heart,” he says, and when you hear the warmth of music through his oak walls, you believe him.

Visitors rarely notice the walls or ceilings of the Navickas home. Their eyes are caught instead by the furniture – the carved patterns, the fluid forms that seem to grow out of the floor. The house itself feels like a Gaudí building translated into Lithuanian nature: soft lines, organic ornament, the quiet strength of a tree turned into architecture.

Beyond his furniture, Rimas dreams of building a spherical, straw-domed house, entirely ecological, warmed by design rather than fuel. “A 300-square-meter straw house will use as much energy as a 100-square-meter conventional one,” he says. He wants it to breathe, to live in harmony with the earth, to prove that art, architecture, and sustainability can coexist.

Rimas Navickas is not only a craftsman – he is a philosopher in wood, a sculptor of light and life. His furniture invites touch and contemplation, carrying within it the principles of nature, the calm of feng shui, and the organic imagination of Gaudí. His oak lace is more than a style; it is a language of devotion, a dialogue between man and tree.

In every curve of his tables, in every grain of his chairs, there is the same quiet message: that beauty and purpose can share one body, that nature offers the best geometry, and that love – for family, for craft, for the living world – is the truest material a maker can use.

Reply