Yael Mer and Shay Alkalay are the Israeli designers who founded Raw-Edges in London in 2007, after completing their degrees at the Royal College of Art. Since the start, the studio has moved comfortably between industrial products, limited editions, and larger spatial installations, with a practice that treats experimentation as the main engine rather than a side hobby.

Raw-Edges’ Engrain Collection is a sharp example of how Yael Mer and Shay Alkalay turn a material test into a full design statement. At first glance, the pieces read like wood furniture wrapped in a bold checked textile. Look closer and the effect is stranger than that – the colour is not painted on, and it is not a thin surface treatment. The pattern comes from the wood itself, with pigment carried through the grain so the colour lives inside the material.

The idea grows out of a simple observation: trees already move water and minerals through their internal structure, so dye should be able to travel through the same routes. In the Engrain process, timber is soaked so colour migrates into the wood rather than sitting on top of it. That means the colour is not “fragile” in the usual way. When the material is cut, sanded, or carved, the colour remains, because it is part of the block.

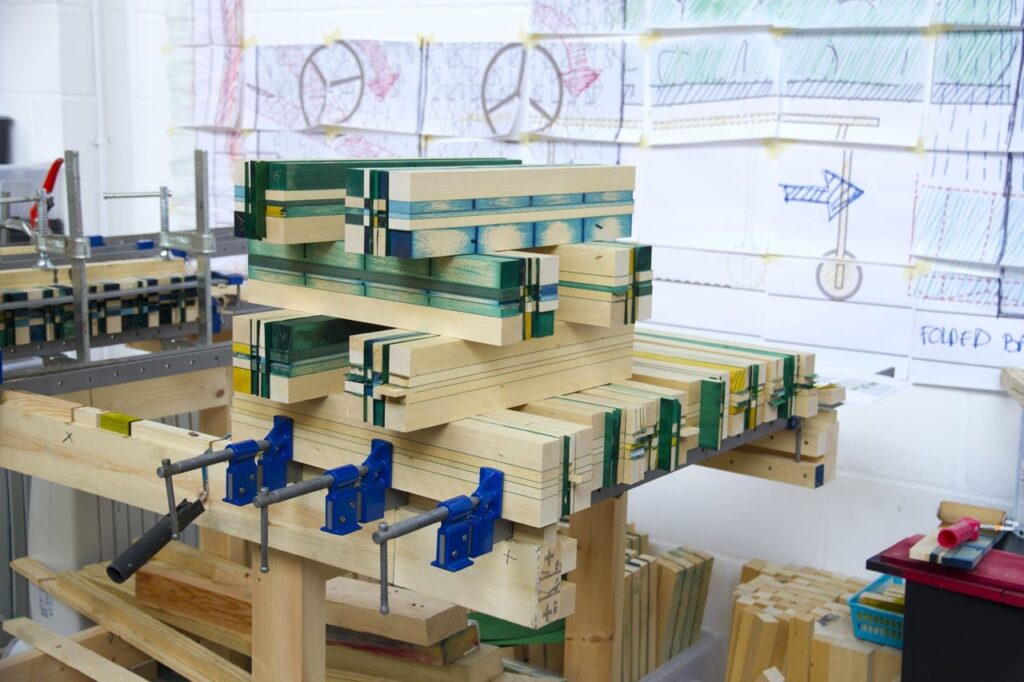

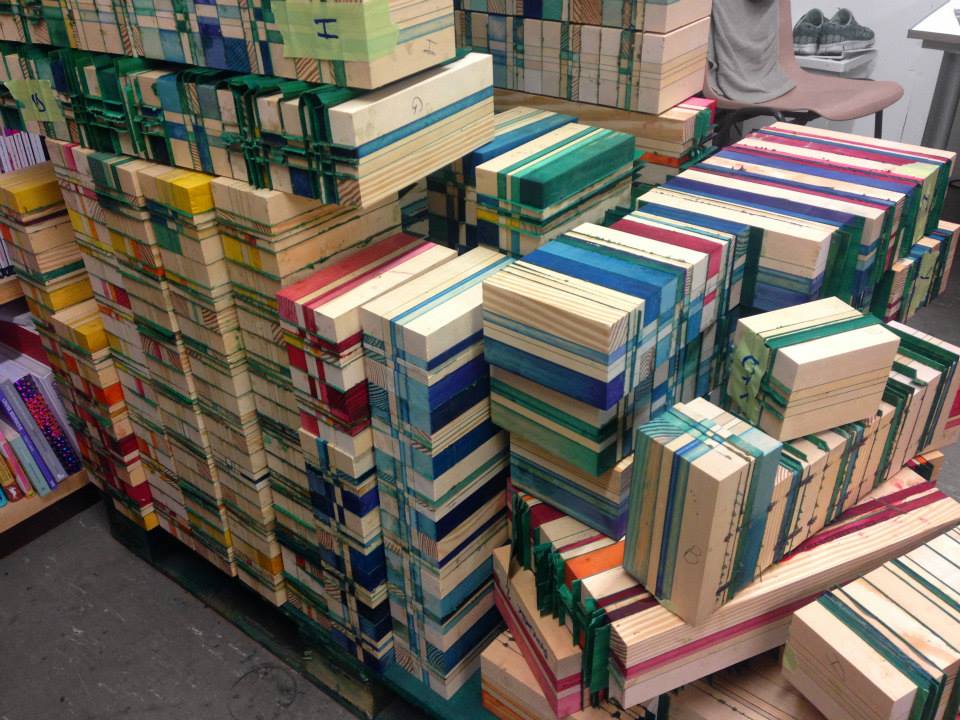

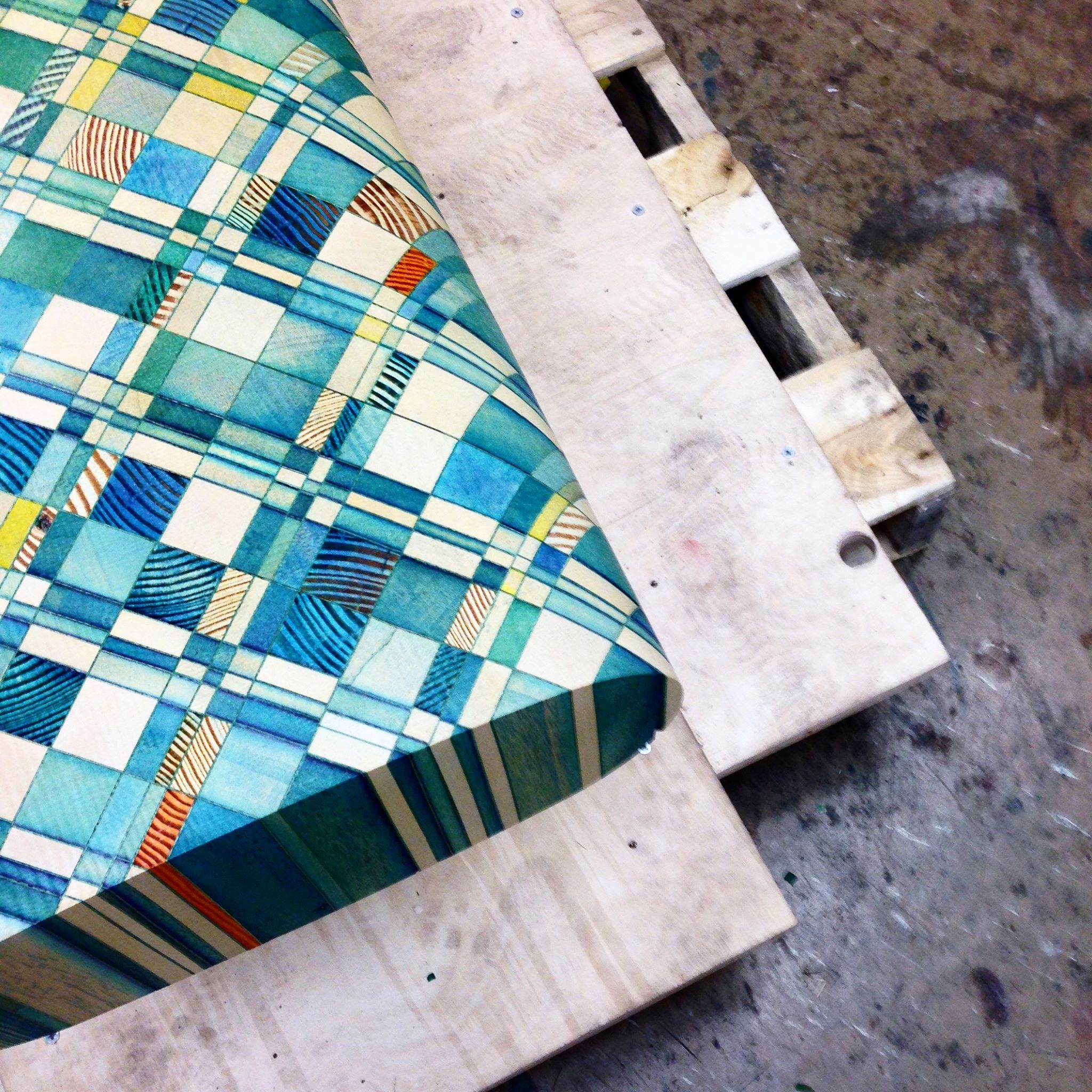

Engrain takes this technique and pushes it into graphic construction. Different coloured elements are prepared and then laminated together into a larger block. From there, the form is shaped by carving and milling, revealing the internal colour structure as the object emerges. This is where the collection gets its signature look: a flat grid becomes distorted when it is turned into a three-dimensional volume. The checks stretch around curves, tighten at edges, and shift direction as the shape slices through the layered block. It feels almost like the pattern is moving, even though it is completely static.

The collection is often shown as a small family of pieces, including a bench, an armchair, and a console table. Each object is a kind of demonstration platform. On the bench, the pattern can read like a long continuous band that ripples as the geometry changes. On the armchair, the checks bend around the seat and arms, creating a tension between softness of form and crispness of the grid. The console table is especially playful, because it treats the pattern as something to be “read” from multiple angles. With reflective elements, the piece can appear visually extended, as if the object continues beyond its physical limits.

There is a disciplined logic behind the fun. The designers set rules: the grain direction, the colour layout, the size of the blocks, the depth of the carve. Once those rules are in place, the final look is created by the cut itself. Instead of decorating a finished object, they design the object so decoration becomes impossible to separate from structure. That is why Engrain feels more convincing than a painted pattern. It is not a graphic imposed on wood. It is wood behaving like a graphic.

Engrain also lands in a wider Raw-Edges theme: taking something familiar – like a checkerboard – and making it feel newly physical. The pattern references textiles and weaving, but the result is closer to sculptural marquetry, telling you exactly how the object was made. In a design world full of surfaces pretending to be something else, Engrain does the opposite. It shows you the inside, then makes the inside the main event.

Reply