There’s something quietly remarkable about discovering an artist who bridges the gap between ancient craftsmanship and digital-age thinking. Han Hsu Tung, a Taiwanese sculptor, represents exactly that intersection – someone who took traditional woodcarving and asked it to speak the language of the modern world. His sculptures have appeared in galleries from New York to Paris, Seoul to Los Angeles, yet his approach remains rooted in something deeply human: the desire to tell stories in wood.

The story of how Han became a woodcarver is not one of privilege or obvious calling. After graduating from National Taiwan University in 1985 with a degree in anthropology, he could have pursued a comfortable academic path. Instead, he chose something far less certain. By day, he worked whatever jobs he could find. By night, he carved wood for three and a half years, teaching himself the craft through relentless practice and observation. It wasn’t until 1991, after his first exhibition in Taipei found an unexpected audience, that he could begin considering himself an artist rather than a dreamer.

For nearly two decades, Han’s work focused on what might be called social realism in wood. His early pieces depicted historical figures and everyday people from the late Qing Dynasty – moments frozen in time, characters caught between tradition and transformation. His “War Series” stands out among these works, a collection driven by deep emotional conviction. Born into a military family, Han channeled his thoughts about conflict and loss into sculptures that captured the humanity of unknown soldiers. These pieces reveal an artist who sees wood not merely as material, but as a vehicle for preserving memory and expressing compassion.

Then, around 2010, something shifted.

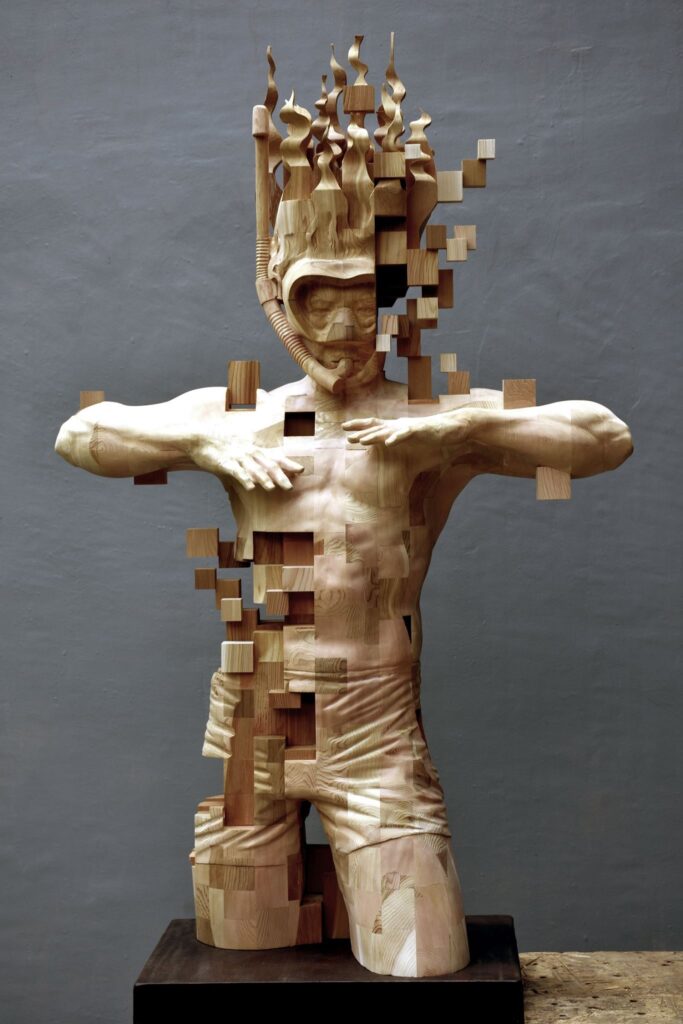

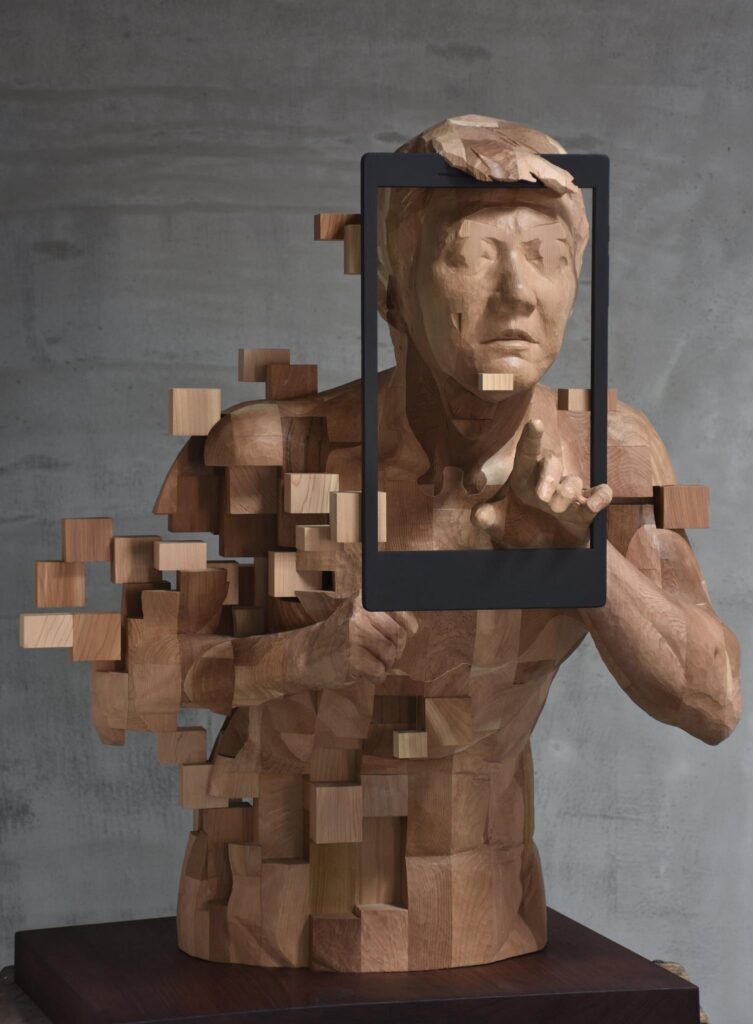

Han began experimenting with what would become his signature style: pixelated wooden sculptures. The inspiration came from an unexpected place – he was simply observing how digital screens are built, how images dissolve into pixels when you look closely enough. What struck him was the philosophical resonance of that dissolving effect. In a world increasingly dominated by screens and digital experience, what happens to the notion of human form? Can fragments and incompleteness still convey wholeness and meaning?

The turning point came personally when his father passed away approximately fifteen years ago. In grief and reflection, Han began carving with wooden blocks instead of traditional methods. He wanted to use recycled and reclaimed materials, transforming them into something unexpected. The pixelated approach emerged not as mere technique but as genuine artistic philosophy.

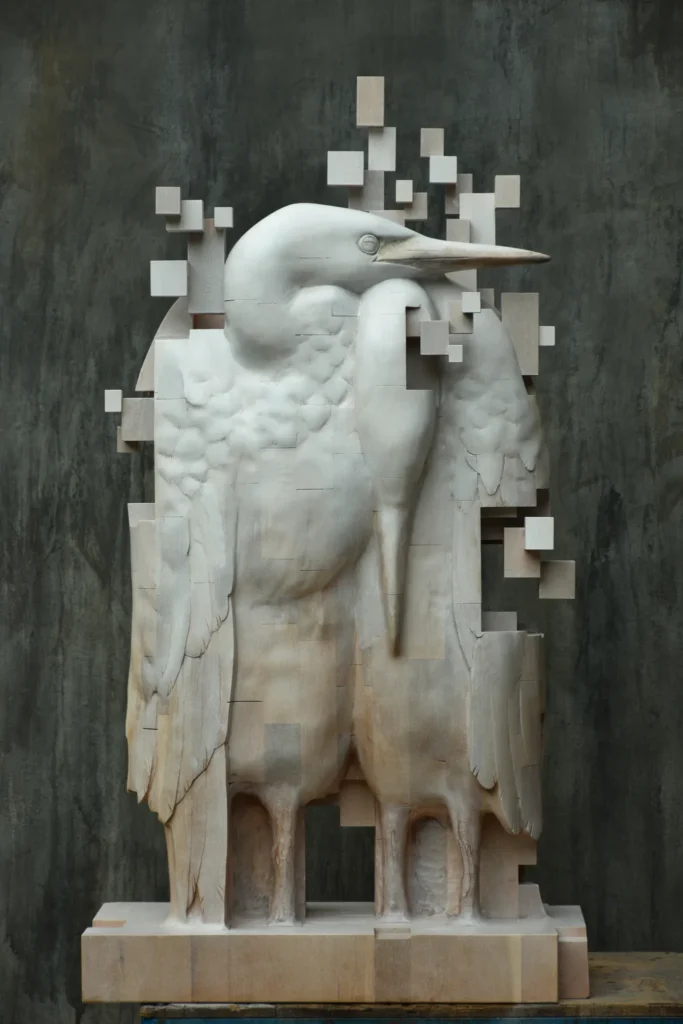

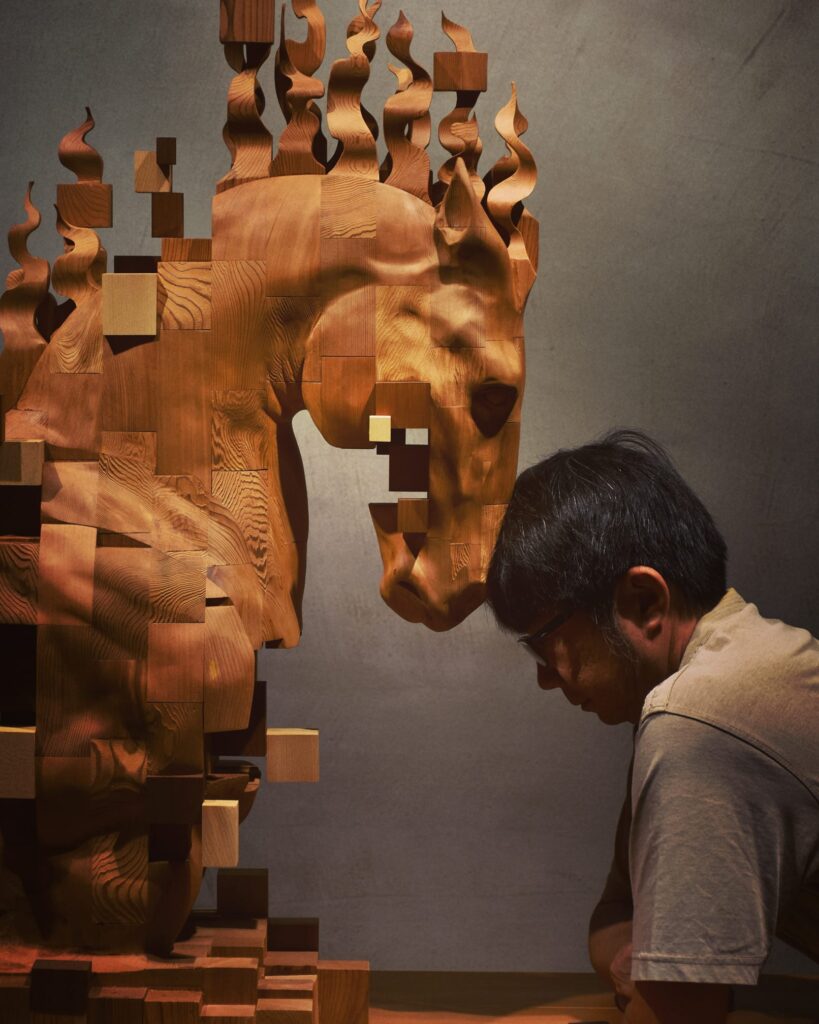

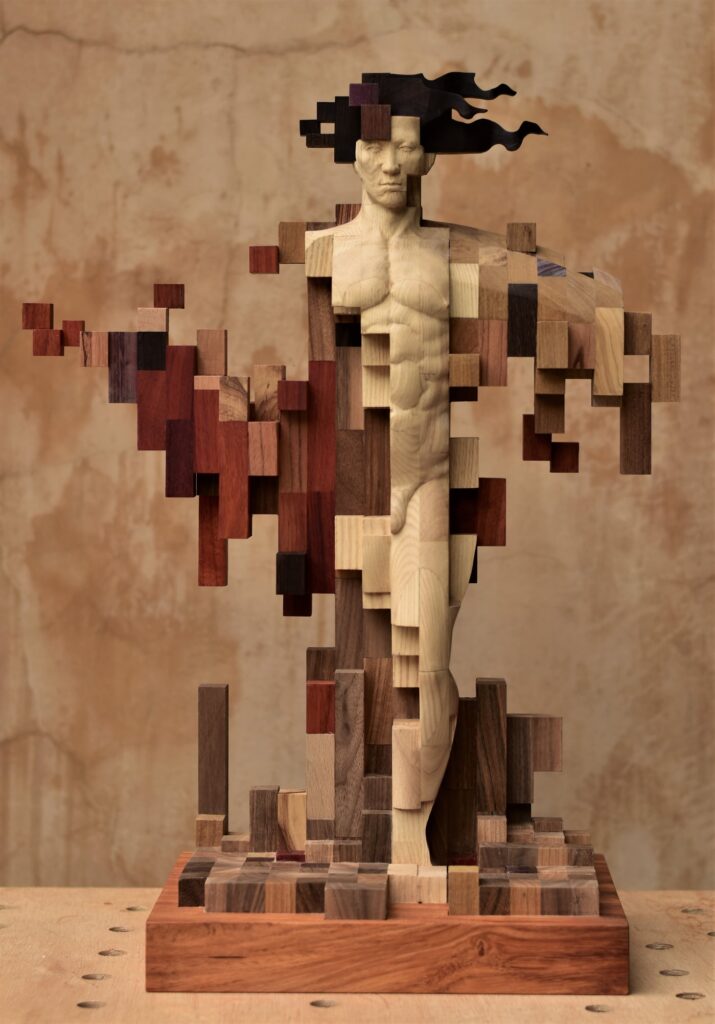

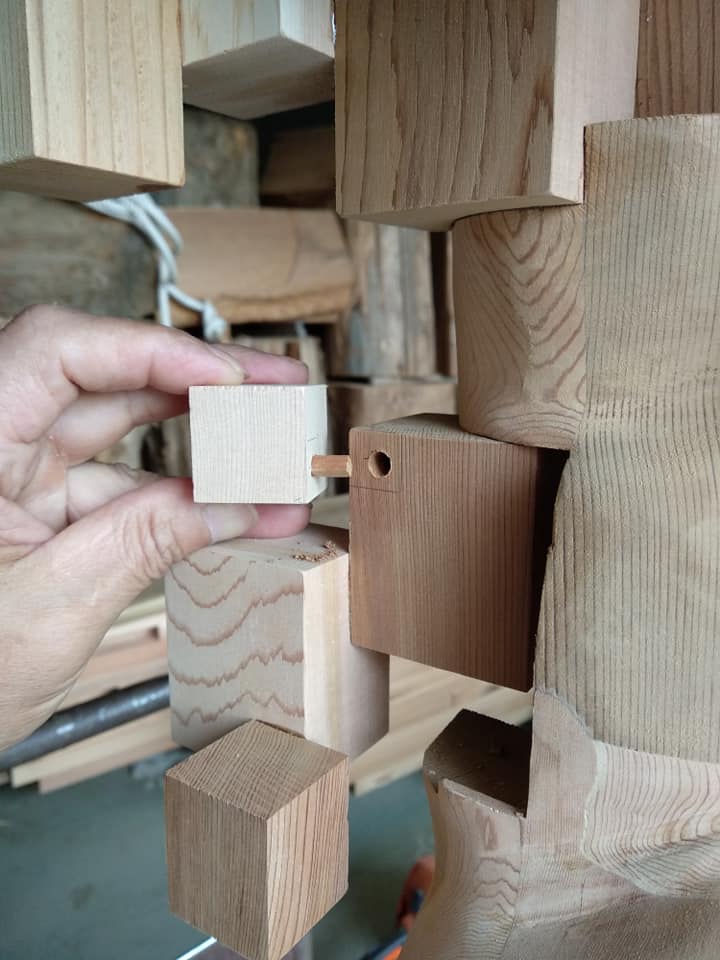

Creating these sculptures is an extraordinarily demanding process. Each piece requires three to four months of meticulous labor. Han typically works with materials like walnut, teak, African waxwood, western redcedar, and Laotian fir. The wood is cut into small cubes – his hand-carved pixels – which are then arranged according to his vision. These individual blocks are carefully assembled, positioned to create the sense that the figure is simultaneously present and dissolving, solid and fragmented. Some areas of the sculpture maintain full definition; others fade into geometric abstraction, creating what feels like a visual glitch in reality.

The technical execution requires tremendous skill. Han begins with clay models and detailed sketches, mapping out exactly where the pixelation will occur, how large the “pixels” should be, and how they’ll transition from solid carving to open space. Only then does the actual woodwork begin – a process involving precise cutting, strategic removal of material, and structural assembly that holds everything in place. Each block must fit perfectly; each gap must serve the overall composition.

What makes Han’s work resonate beyond its obvious technical achievement is the conceptual depth. These pixelated figures aren’t simply “broken” or corrupted. Instead, they explore the tension between analog and digital, between human experience and technological mediation. A face that dissolves into wooden cubes seems to ask: In an age of screens and algorithms, what remains of authentic human presence? His sculptures titled “Where is the Like” and “iFashion” make this commentary explicit, directly engaging with social media culture and digital identity.

The thematic range is impressively broad. Han has carved figures of baseball players frozen in action, their bodies vibrating with energy even as they fade into abstraction. He’s created portraits of men and women caught in moments of contemplation or movement, each piece telling a story of the human condition. Animals appear in his work as well, suggesting that his interest in digital fragmentation extends beyond the strictly human to encompass all living things.

What’s particularly striking is Han’s approach to sharing his knowledge. Rather than guarding techniques like precious secrets, he actively posts his work-in-progress on social media, showing followers the meticulous carving process, the way wooden sheets are glued together, the patient chiseling that gradually reveals the final form. This openness speaks to his character – a belief that art should serve community and that helping others develop their vision matters more than maintaining mystique.

In recent years, Han has pushed his practice even further. Around 2019, he became fascinated with electric motors and programming languages, wondering whether he could introduce kinetic elements to his sculptures. The idea of his work actually moving, of those pixelated elements potentially rotating or shifting, represents another frontier in how he’s interrogating the relationship between craft and technology.

Han Hsu Tung represents something increasingly rare in contemporary art: an artist who refuses to compromise or chase trends. He doesn’t take commercial commissions that demand compromise, and he’s unwilling to sacrifice his vision for quick success. Instead, he’s spent three decades developing his voice, allowing it to evolve naturally from social realism to conceptually sophisticated digital-age statements carved in wood.

His sculptures invite us to pause and consider what we’re looking at – not just the technical achievement or aesthetic pleasure, but the deeper questions about presence and absence, permanence and dissolution, tradition and transformation. In galleries around the world, his wooden figures stand as quiet reminders that even in an age of infinite digital reproduction, something made by hand, carved patiently over months, speaks to us in ways that pixels on a screen simply cannot.

Reply